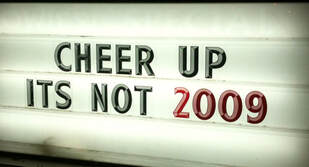

When people try to offer a supportive statement to a friend or loved one who has just received tragic news, they generally mean well. Unfortunately, many lack experience in this role, try too hard, or take approaches that fail to comfort the individual in pain. To help prepare you for the next time someone seeks your comfort following a relationship breakup, death of a loved one, diagnosis of a serious illness, layoff, or other crisis, we have developed an expanded list of “what not to say,” followed by some better alternatives. Important disclaimer: No one is expected to automatically know how to be supportive in a crisis, and we have all uttered less than helpful statements at some time. If you encounter any of your own past remarks, give yourself a pass on those, gather new information to make adjustments for future situations, and avoid judging yourself.  Ever notice that when your team is losing, cheerleaders don’t cheer up anyone? Ever notice that when your team is losing, cheerleaders don’t cheer up anyone? Blindly optimistic predictions Successful grieving and adjustment to loss relies heavily on time. Initially, it is normal to feel shocked, sad, hurt, drained, angry, overwhelmed, bewildered, or even unrealistically hopeful (e.g. denial). Only after swimming around in these states for a period of time can a person move toward accepting a loss, at which point she can begin to be genuinely hopeful about the future. Therefore, offering a prediction of a brighter tomorrow to someone who has just suffered an excruciating loss will tend to provoke feelings of annoyance, and a sense of not being heard or understood. Consider removing the following predictions from your repertoire: X Everything will be okay X You will bounce back in no time X You will get through this X There’s another soul mate/ ideal job out there for you X You will come out of this stronger than ever X You will feel better in the long run X Life goes on Despite good intentions, attempts to promote hope and optimism at an early stage are risky and usually counterproductive. For instance, following certain tragedies, things may never again be “okay.” Even in less severe circumstances, life may go on, but it may be fundamentally changed. If your goal is to offer real support, you have better options available than making predictions.  Your will to cheer has no effect on me Your will to cheer has no effect on me Encouraging—but unwanted—commands People with a direct or commanding interpersonal style sometimes step in the trap of trying to order their suffering friends and family to cope. Again, they mean well, and often base their advice on their own past, successful efforts. However, just like with blind optimism, people usually won’t appreciate commands when they are struggling with the depression, anger, denial, or bargaining stages of grief, so statements like the following will not resonate: X You just need to keep going X Get back out there X Pray hard, and good things will happen X Just do ____, and you will feel better One more reason to avoid commands: just because an active, ambitious approach to recovery helped one person move on from a loss does not mean that style will work for everyone, especially in the early stages of grieving.  You didn’t REALLY need that left arm, did you? Aren’t you right-handed? You didn’t REALLY need that left arm, did you? Aren’t you right-handed? Devaluing the loss What would happen if the grieving individual realized that what they lost wasn’t so significant? That’s the logic behind devaluing: if we can convince him that he will be better off without the lost person, job, relationship, etc., then maybe he won’t hurt so much, right? In the immediate aftermath of a loss, devaluing actually has the opposite effect, motivating the individual to defend or hold onto the loss, and taking your statement as an empathic failure rather than as support. No matter how much evidence you may have to support these ideas, for the sake of your relationship, don’t utter them out loud: X S/he didn’t deserve you X You can do so much better X You didn’t seem very happy with that person/ job anyway X He/ she/ that position had a lot of flaws X Didn’t ____ used to treat you badly? X This might be the wrong time to say this, but I never really liked _____ Besides provoking anger and defensiveness, devaluing can also add a layer of judgment on top of pain. That is, if an individual bought into the logic of devaluing, then in addition to experiencing grief, he might also judge himself harshly for assigning so much value to the lost relationship or job in the first place.  Well, since you put it that way, guess I have no right to be sad Well, since you put it that way, guess I have no right to be sad Misguided use of contrast and perspective This strategy follows logic similar to devaluing, but instead of focusing on the loss, it tries to highlight what the person still has and how things could be worse. Ironically, people who are grieving often use contrast and perspective to comfort themselves from painful feelings associated with loss. Sometimes, this approach—a form of bargaining—is necessary to help them maintain basic functioning in daily life activities, but still postpones inevitable pain. Grieving individuals are entitled to think in these terms when they need to get through the day, but for the rest of us, sharing these thoughts needs to be off limits: X Well, at least you still have___ (your other pet, parent, sibling, or child; friends; a job; a roof over your head; the use of your other arm)– Imagine how many people don’t even have that! X Things could be worse. You could have lost ___ (see previous examples) X It’s just fate, Karma, God’s plan, etc. X Everyone is hurting over this X If I could get over ___ (my past loss), I’m sure you will survive this X Studies show that people generally get over ___ (your loss) In most cases, these ill-advised attempts to relieve another person’s suffering end up causing more of it.  I want to be annoyed with you, but I just can’t I want to be annoyed with you, but I just can’t Empathy and action always beat sympathetic cliches When faced with a friend’s or loved one’s pain, it’s easier to be supportive if we hold onto one perspective: what does the affected person need from me to feel comforted? You don’t need to search for some remark that magically takes away pain. You won’t find one, and no one will expect this from you. In most cases, people want to feel that you are present, listening, understanding, and accepting them without judgment. All this requires from you is to be attentive, listen, accept their feelings, and keep things simple. The following are supportive comments you could make in the wake of significant loss: √ I’m sorry √ That is so sad √ You must be hurting/ in pain √ That person/ job/ pet clearly meant a lot to you √ It must be so hard not to have that ___ (job, person, ability) anymore √ I’m here for you √ How can I help? √ What do you need from me? √ What is the best way for me to be supportive to you? √ There may be resources available to help you during times like these Finally, you don’t always have to rely on words to support people who are grieving. Actions can feel just as supportive, sometimes more (depending on individual preferences). Use your discretion when offering the following supportive acts: √ Show up, spend time with the person √ Give a hug √ Supply a meal √ Offer to perform a necessary task that relieves burden from the affected person (shopping, transportation, errands, phone calls, chores, etc.) √ Identify other supportive individuals and ask them to get involved √ Mark your calendar for significant future dates–birthdays, holidays, wedding anniversaries, Mother’s/ Father’s Day, anniversary of a loved one’s death, etc.–and show up again  I don’t even need capacity for language to comfort you I don’t even need capacity for language to comfort you People who have recently experienced loss often experience strong feelings, such as shock, sadness, anger, fear, or hopelessness. In addition, they may feel compelled to repeatedly share a story or sentiment. As their supporters, it is not our job to predict, prevent, or change those feelings. Such emotions are normal and to be expected, under the circumstances. If we allow people to experience or express those feelings, without judgment, then they will feel our full support. Sometimes, just listening—without any obligation of response—is exactly what people need during their most challenging moments.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

The Solutions Mine BlogAll articles written by Jason Sackett, PCC, LCSW, CEAP. Archives

July 2021

Categories |

Services |

Call310.251.2885

|